By a timely coincidence with our latest research summary on parasympathetic dominant overreaching, Cycling Weekly has published an article this week on adrenal fatigue and how it affects your training and performance. For anyone who trains frequently and doesn’t have access to the full article, which is based on an interview with Dr Tamsin Lewis (herself an accomplished IM Triathlete), here’s a summary of the key points:

Though ‘adrenal fatigue’ is not an accepted term in the medical community, malfunctions of the stress response system are a very real phenomenon. The sympathetic branch of the nervous system activates production of fight or flight hormones, including cortisol.

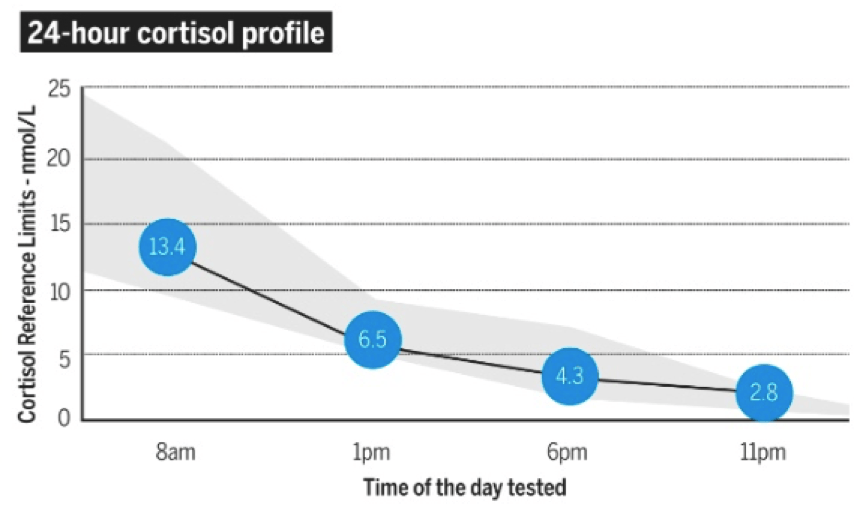

Evolution designed us to have a fast reaction in order to cope with challenging situations, but the problem is that modern life, combined with high volumes of training blunts the responsiveness of the system. Cortisol is responsible for waking us up in the morning, and usually declines steadily throughout the day:

The problems are compounded by mental / emotional stress, poor diet and sleep quality. Training at over 80% of VO2 max places considerable demands on this system and ultimately the adrenal glands stop producing cortisol and the daily profile becomes flat.

Symptoms include:

- Disturbed sleep and night sweats

- Low immunity and allergies

- Inability to concentrate

- Muscle soreness and excessive urination

- Low sex drive

The lack of sympathetic drive means that your resting heart rate is likely to be lower than normal, and HRV higher than your normal range. These effects are discussed in more detail in the research summary. A number of professional teams measure salivary cortisol levels in addition to resting HR and HRV in order to make a confident diagnosis.

The real key is not to let the condition develop in the first place, as it can be debilitating and takes months to recover from.

Recommendations for recovery include:

- A really healthy diet, including sufficient carbohydrates, good fats, salt and appropriate supplements (these need to be based on diagnosis of deficiencies eg from blood analysis).

- Getting enough sleep, and paying attention to sleep hygiene.

- Training polarization – cut back the hours but make the hard sessions hard and the easy ones easy. It’s actually high volumes of the middle range tempo work which is least productive (see our infographic).

- Reduce intake or take a break from caffeine. Needing large amounts to get going is not healthy in the longer term.

- Stress less and learn to relax – easy to say, but Yoga, deep breathing and spending time with friends are all proven ways of reducing the stress load your body experiences.

- Using daily HRV readings to tailor your training to what your body is capable of accommodating that day.

By Simon Wegerif

Another great article and great advice. Thank you. I have been trying to implement these 6 steps for some time but it is good to see them linked to recovery like this.

Thanks for the post, Simon. Spoke to me directly!

Training polarisation might be a bad idea. Better train only cautiously. High wights can be okay but not as high as you get excerted, not a bit excerted!

In my case, as soon as my training hits a certain intensety (e.g. HIIT/burpees) even for only 30 seconds my symptoms are back for at least 3 days (sleep only 2 hours, wake up wet of sweat, hearts beating super loud, taking sleeping medication, sleep for anather 2 hours, etc… ).

I’m having this extreme condition for 2 years now, and it stays that way. (I guess the adrenals are defect for way longer but I didn’t know better back than. I couldn’t sleep through for years. Only after a rough year and thyroid problems, because I couldn’t get my medicin due to supply problems because of corona, my adrenal problems skyrocketed). As soon as I try HIIT again or have to much fun in the sports class I suffer for days from unrestorative, stressful sleep and unconcentraited days – and with that comes sadness. So be aware of your training!