Science & Cycling is an annual gathering of researchers, expert practitioners and team performance managers arranged a couple of days before, and close to the start of the Tour de France. It was our first time attending and exhibiting and turned out to be one of the most intense conferences I’ve ever been to.

Science & Cycling is an annual gathering of researchers, expert practitioners and team performance managers arranged a couple of days before, and close to the start of the Tour de France. It was our first time attending and exhibiting and turned out to be one of the most intense conferences I’ve ever been to.

As well as a packed two-day academic program, there were bike fit and injury prevention masterclasses together with a social evening.

As well as a packed two-day academic program, there were bike fit and injury prevention masterclasses together with a social evening.

The presentations

There were too many presentations to summarise but I want to give a few of the highlights that I particularly enjoyed.

Day 1 began with a series of keynote speeches. Marc Quod of Orica – Greenedge talked about two applications of science to his team practice. The first explored what happens to a world tour cyclist’s performance when they adopt a high fat diet? Once adapted, the rider’s power outputs were not greatly affected, but what was really interesting was that when carbs were reintroduced on a periodised basis (i.e. when needed for intense training and racing) the rider’s performance increased significantly even compared to the time before they went on the high fat diet. This suggests that the high fat adaptations were retained and improved his ability to use multiple types of fuel. Marc also mentioned their use of a model called W’ Bal (available in Training Peaks and Golden Cheetah) which allows riders to see how much energy they have left in the tank. Although promising, it has still some way to go before you can work out exactly when your uphill attack is out of gas!

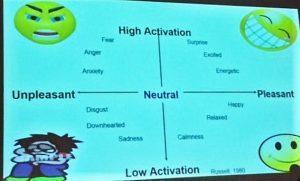

Sports Psychologist Professor Andy Lane talked about using emotions to generate energy. He described the mood map which was the inspiration for the ithlete Pro Training Guide:

Everyone experiences emotions such as anxiety and anger in competitive situations, and these have a purpose, but they need to be understood to avoid them leading to poor pacing decisions or a lack of confidence. Andy described alternative strategies such as ‘self talk’ and ‘visualisation’ which can help you manage and channel emotional energy into your performance.

Fred Grappe, Head of Performance at the FDJ team expanded on the topic of effort perception experienced by cyclists explaining that the brain continuously compares the anticipated sensations from a level of effort with those actually experienced. He went on to describe how even at the professional level, the relationship between power output (PO) and rating of perceived exertion (RPE) varies from day to day and that this variation could be attributed to factors including the current point in the training cycle, environment conditions, mental fatigue and stress, as well as dissociation strategies i.e. the idea that when intensity is low, you may want to appreciate every motion in your body as a smooth machine, whereas at high intensity you may want to dissociate as much as possible from the sensations coming from your screaming legs!

Andrea Zignoli presented a very interesting talk about HIT interval design. Usually, the duration of each interval and the rest between intervals is kept constant in a session, but Andrea has developed a model which can accurately predict blood lactate levels and used this to show that the anaerobic training stress could be better administered by taking only a short break between the first and second intervals, then a much longer break between second and third to allow lactate levels to decrease to an acceptable level before going again.

Romain Meeusen talked about the brain and performance, arguing that what we feel as we get tired during exercise is really all down to neuro chemistry. The human brain is a very hungry organ, using 130 grams of glucose per day, which it converts to lactate for fuel. It is now considered that fatigue sensations are closely coupled to a lack of glucose – something that many of us can relate to from the almost instant revitalization a carb gel brings during long events. The mere presence of carbs in the mouth is enough for the brain to release some of its stores in anticipation of refilling very soon. The brain also supercompensates post exercise and mops up most of the carbs that are taken in first.

Lesley Ingram described studies she has done on sleep disruption, recovery and the immune system, showing that after one night of disrupted sleep, athletes have a measurable reduced performance, but that interestingly, their immune systems actually stepped up activity, presumably as a way to help prevent infections taking hold during this stressed state. This is not a carte blanche to go without sleep and expect not to get sick though, as Lesley plans further studies on what happens to the immune system after several nights are disrupted!

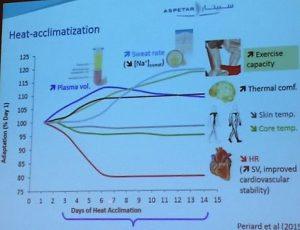

Julien Periard explained the process of heat acclimatization in detail. Moving through the air quite quickly, cyclists lose heat through conduction and radiation, but it is sweat evaporation that does most of the work when the outside temperature is above 30C. This requires a lot of water & salt leading to dehydration if these are not replaced fast enough. Acclimation begins with an increase in plasma (blood) volume during the first 5 days but the sweating mechanisms only reach maximum efficiency after 10 days.

Sebastien Racinais complemented this talk by providing practical advice on acclimation techniques, and advised cyclists preparing to compete in the heat to spend at least an hour a day for 7 days before their event in comparable heat and to exercise inducing sweating to cause adaptation. He advised starting the event over hydrated and to include sodium (salt) supplementation. An interesting tip was to drink an ice slushie before the start, since melting the ice takes a lot of heat from your body – much more than just warming water from 0C (it’s called enthalpy!).

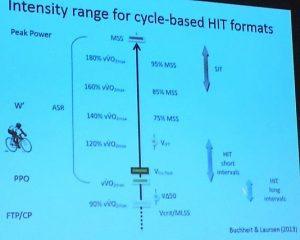

Paul Laursen presented some of the latest thinking on HIT training – a subject he has been studying and writing on for many years. He emphasized that individual responses to HIT vary and the most effective formula needs to be found for every athlete. Prof Laursen has also been an advocate for maintaining health as well as fitness, has co-authored a number of papers on heart rate variability (HRV) and has been a supporter of ithlete since shortly after we started in 2010, so it was great to spend some time with him face to face.

Speaking of recovery, there were a couple of papers making nutritional recommendations, for instance the best times and doses for protein ingestion: amazingly it takes only two hours for milk protein to start becoming part of your muscles, and exercise increases the rate at which new muscle cells are created. It’s a good idea to take 20-25g protein with each main meal, but most important is immediately after training.

Bryan Saunders revealed some truths about caffeine and performance, most of which is mental i.e. caffeine reduces your perception of effort, but also individual results vary, and it is not necessary to reduce or eliminate caffeine in the run up to an event or competition (phew!).

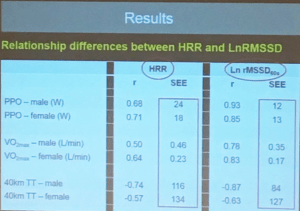

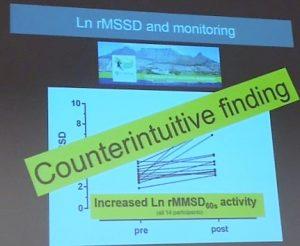

Last, but by no means least, Prof Robert Lamberts from Capetown Uni dispelled some of the myths around HRV, showing that, given a good protocol and suitable measures, that HRV can be a reliable index of parasympathetic activity and predictor of exercise performance. He organised a study of various measurement lengths, and found the 60 second measure of LnRMSSD (as standardized by ithlete) to be the most reliable, compared to both longer as well as shorter measurement times. HRV was found to be a better predictor of performance than Heart Rate Recovery (HRR) which is sometimes used as an indicator of fitness, in both athletic and general populations. All very encouraging!

Robert also brought out into the open a phenomenon we have observed many times over the past 5 years, that is a counter-intuitive rise in HRV after a strenuous event or series such as a multi-day race or training camp (I experienced this myself after the Haute Route Alps 6 day race). Although not fully explained yet, Prof Lamberts thinks it is probably caused by a combination of an increase in plasma (blood) volume, decrease in sensitivity of adrenaline receptors and possibly a decrease in production of catecholamines (the adrenaline family hormones). Nonetheless it is definitely a fatigue state, and is signaled by the ithlete Pro Training Guide, where you can get an amber in the bottom right of the chart.

Overall a very stimulating event, where we met up with several research contacts and customers and made a number of new friends. Bring on next year in Dusseldorf!

Simon, can you post a copy of “Prof Robert Lamberts from Capetown Uni” paper?

Thanks

It’s not published yet, but Prof Lamberts has promised me a copy as soon as it is approved.