Who, what & why?

Most endurance athletes are familiar with the term ‘overreaching’. That’s when you do high volumes of intensified training, to cause supercompensation. Although ultimately you get fitter and stronger, during overreaching you get a very tired body and muscles, and your performance starts to decline noticeably. You may also notice sleep and mood disturbances. Not much fun. But what actually happens to your body and what measures can you use to identify when overreaching has gone too far and become unproductive?

That’s what an experienced team of Australian and South African researchers set out to confirm. They had an idea that the commonly reported decrease in Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR) in athletes that are confirmed as overreached, together with changes in body composition and appetite might hold clues as to what is really going on in this state.

What did they do?

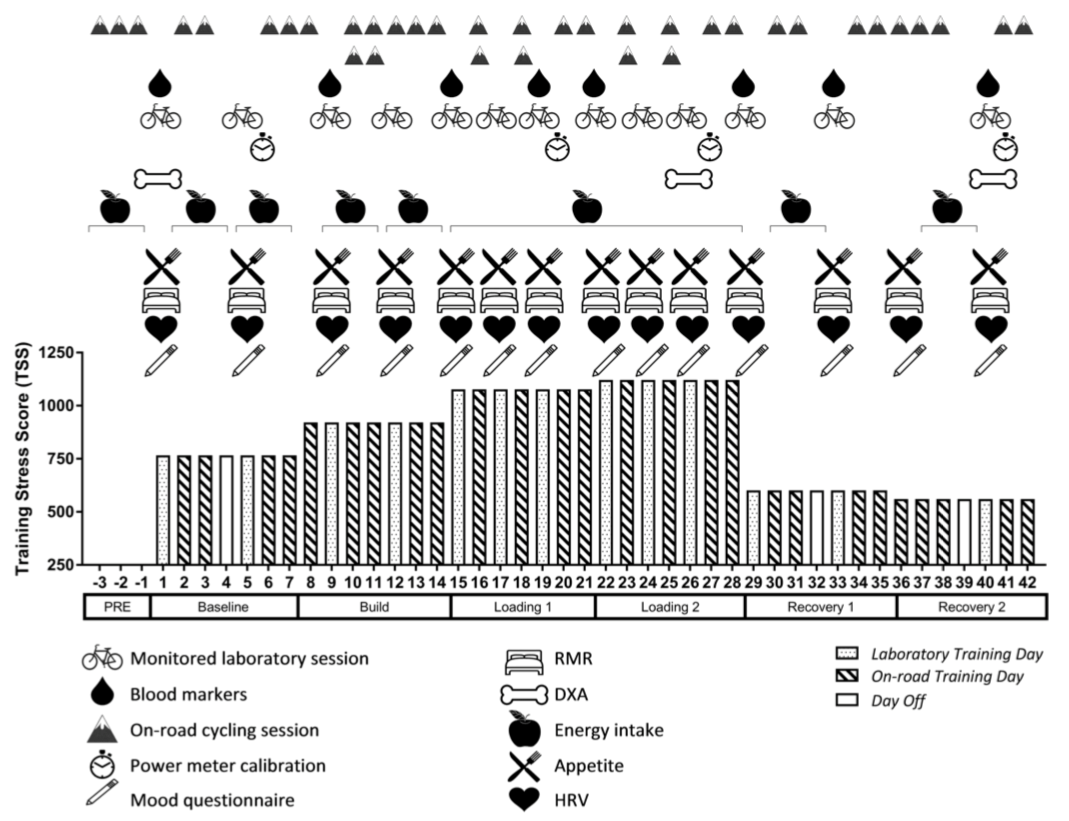

Thirteen trained male cyclists completed a six-week training program consisting of:

- A “Baseline” week (100% of regular training load),

- A “Build” week (~120% of Baseline load),

- Two “Loading” weeks (approx. 150% of Baseline load)

- Two “Recovery” weeks.

Training comprised of a combination of laboratory-based interval sessions and on-road cycling. RMR, body composition, energy intake, appetite, heart rate variability (HRV), cycling performance, biochemical markers and mood responses were assessed at multiple time points throughout the six-week period, as shown in the figure below:

Lab training sessions consisted of a warm up followed by a high intensity session on a Wattbike. Each on-road training session comprised of a long aerobic ride and later that day a series of hill repeats at Functional Threshold Power intensity (the maximum power you can sustain for 1 hour). Training loads were all monitored with calibrated power meters and converted to Training Peaks TSS training loads. The researchers took a lot of care to ensure that all the cyclists were performing the required training loads at each stage.

What did they find?

Reductions in aerobic and anaerobic performance, together with mood disturbances confirmed that all the cyclists had indeed become overreached.

The intensified training period brought on significant decreases in resting metabolic rate, HRV and body mass, which returned to baseline during the 2-week recovery period.

Whilst some of the reductions in HRV were modest, others were dramatic, going from mid 80s on the ithlete scale to mid 40s at the end of the loading phase. However, all the cyclists’ HRV values were lower at the end of the intensified period compared to baseline, and all but one had recovered close to or above baseline by the middle of the second recovery week.

They also noticed a decrease in the cyclists’ appetite during intensified training, but did not find any of the expected changes in either Leptin (the hunger hormone) or thyroid activity.

What does it mean?

Although the researchers had hypothesised a strong connection between energy intake, hormone levels and resting metabolic rate during intensified training, and had conducted the study very carefully, they did not find all the relationships they were looking for. They were able to conclude though that multiple metabolic changes do likely result from the body’s attempt to preserve homeostasis when energy demands of training are significantly increased.

They recommended that, especially during periods of intensive training, athletes should be encouraged to increase their energy intake in line with planned training loads, rather than just relying on appetite as the signal that energy demands are out of balance. They further recommend that athletes and their coaches should be monitoring energy intake, power output, body mass, HRV and subjective metrics to avoid distress and provide the best chance of positive adaptation.

ithlete provides the recommended LnRMSSD HRV measure used in the study, as well as suitable subjective and recovery metrics that will allow you to monitor these aspects. Although the study used cyclists, the principles will be equally applicable to other endurance sports such as running, rowing, and cross country skiing.